Electronics and computer-based technologies are integrating into our society at an ever-increasing rate, and – despite the potential for them to be abused – I find myself excited at the possibilities of what can be achieved with the latest developments in those areas. I am especially fascinated with wireless technology. Unseen energy being utilized to accomplish various tasks using WiFi, Bluetooth, RFID and NFC. It’s like magic to me!

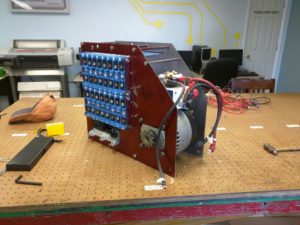

Our Makerspace uses RFID tags to control access to the building. To enter, you scan your tag, enter a PIN (personal identification number) which is verified against the list of access credentials on TCMS’ server, and upon verification a relay is energised to unlock the door. This system benefits the Makerspace in terms of both cost and administration, as RFID tags are cheaper than making keys for everyone and as their use gives the TCMS board the ability to track and monitor the level of activity at the Space. One day I accidentally locked my keys inside the building, and needed to wait to be “rescued” by another member of the Makerspace. I vowed that this would never happen again, and remembered that one of our other members had taken what some would say extreme measures to have an RFID chip implanted into his hand! I had been fascinated by the potential applications of this procedure, which include access controls like normal RFID tags. The RFID chip used is about the size of a grain of rice, and is sealed inside a glass enclosure.

I decided to take this idea a step further – I would get an RFID tag implanted in one hand, and an NFC tag implanted in the other hand.

The RFID chip was cheap (~ $10) and non-programmable; it contains a unique PIN, which I had entered into the TCMS access credentials system. I use this chip to gain access to the Makerspace now. It is in my right hand, so I “scan” my right hand at the door, enter the chip’s PIN, and voila – the Makerspace door opens. No more losing tags or keys!

The chip in my left hand is an NFC, or Near Field Communications, chip. This chip cost around $99 from DangerousThings (https://dangerousthings.com/shop/xnti/), and is programmable with my phone using the DangerousThings app (available through the Android apps store at https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.dangerousthings.nfc&hl=en); I have also found the NFC Tools app to be useful. I used this app to scan and program my chip to protect it against accidental locking, which would make it non programmable.

I have added my chip to the lists of access credentials on various trusted devices so that I can, for example, unlock my phone by scanning my tag (tapping my phone to the back of my hand). I have also used the NFC tools app to program my chip to carry my ‘vcard’, or virtual business contact card, which allows me to transfer my contact information (name, phone number, email address, etc. ) to someone else’s phone by tapping their phone on my hand! Unfortunately this will not work on iPhones, as Apple has restricted NFC functionality to be used exclusively with their iPay app; but Android phones permit it so long as their NFC functionality is enabled.

Building further on these basic applications, I’ve loaded a profile (script and data) onto my chip with a link to my resume, so that if you scan my tag it prompts you to download my resume from my website! So cool – I’d hire me! 😀 Finally, I’ve created and loaded another profile to save my personal emergency information (name, allergies, blood type, emergency contact info), which can be transferred to someone else’s phone in a similar way. I am considering getting some sort of tattoo to indicate the implant’s presence to emergency personnel; if anyone reading this has any ideas about how I should go about doing this, please let me know!

I feel like a spy with this kind of technology literally embedded inside of me! I am excited to see the future of implantable technology development and applications, and cannot wait for the day when I can pay for things by scanning my hand!

Picture References:

All pictures and videos provided and owned by Gary Alan Dewey, except for “Quarter and Transponder”. Dangerous Things. Dangerous Things. 4 March 2018. Web. 4 March 2018.